Please click here to subscribe to our unmissable email Newsletter

You will thank me!!

Please click here to subscribe to our unmissable email Newsletter

You will thank me!!

It’s a grey and dreary winter’s day. My thoughts go to Youth Day as I drive down Buffelsfontein road toward my regular Walmer coffee spot. My mind dwells on the sad truth that the passenger seats in my car are all empty. My children have now grown and left this town for a brighter future. No youth in my car this youth day.

My gloomy sadness is interrupted though, by an unfamiliar sight by the side of the road. A makeshift water station on the verge with a number of emergency taps on light blue plastic standpipes. Our answer to “Day Zero,” I am told, has been to drill boreholes in strategic spots and allow people to fill containers of water enough to drink and cook and clean with. Later, over coffee, I can’t help but think, that if ever there was a monument built to mark the failure of government in this town of ours, then these blue standpipes are it. No political argument, no beaming Politian’s picture in the press or free pop concert for the masses can argue away these pipes. They are there standing boldly as monumental evidence of our inability to manage the affairs of this city region. The unavoidable truth is that government is failing at the most basic and fundamental level. Running water and flushing toilets are not rocket science. Running water is the most fundamental and non-negotiable starting point of what we have come to expect from urban living.

I am sorry to tell you though that I really don’t have any answer to the water problem. I’m simply using this very visible failure as an excuse to talk about a question that’s interesting to me right now:

Is it not time we begin to re-ruralise?

Is it not time that we accept that our current system, just does not have what it takes to effectively manage towns and cities? I mean, have you driven down the main road in Humansdorp lately? It’s one continuous pothole. Makhanda has had water problems for years. Mthata is chaos!!

Is it corruption? Is it white monopoly capital? Is it the construction mafia? Is it lazy officials who earn fat salaries but don’t deliver? I’m not interested in those questions right now. I am interested rather to zoom out a bit and consider the slightly larger question of why it is that we, as a civilisation, have decided to build cities and towns in the first place and whether the conditions that seemed to make cities and towns a good idea way back then, still prevail.

I can completely understand why the first towns and cities must have sprung up all those thousands of years ago in Iraq and elsewhere. Back then it was so much easier to get all the cool stuff you needed by living in a city like Eridu. The butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker were all right there. By contrast, your rural cousin had to figure out how to make what ever cool stuff he wanted all by himself. Living in the countryside was a ball ache!

With time, through the growth of civilisation, the industrial revolution and right up to the 21st century, cities became increasingly sexy. The city meant, running water and electricity. It meant education for your kids. It meant music and entertainment. It meant fun church and religious activities. It meant access to more potential romantic partners. It meant access to better health care. City living though (for all but the very rich) came at a huge price. City dwellers contend with crime, bad food, air pollution, overcrowding and worst of all; jobs to pay for all these conveniences and cool stuff. But perhaps the biggest price we paid was the loss of our connection with the land, the fresh smell of rain on the soil and the feeling of being part of the glorious living organism that is our mysterious planet.

What I see lately though is a glimmer of an exciting shift brought about by rapidly advancing technology. A discernible adjustment in focus from urban to rural. Thanks to solar and battery technology, we no longer need to live in a city to run a fridge or computer. Thanks to cheap electric pumps and plastic piping, rural homes can have running water and flush toilets. Very soon, even remote rural areas will have super-fast satellite internet. This will give rural people access to the highest quality education through apps like Udemy, the highest quality preaching for the religious-mined though apps like YouTube. It will give access to a huge pool of potential romantic partners through Tinder and Instagram. Sure, living in the city will still give you somethings that you just don’t get in the country, but I am open to the idea that the scales will begin to tip. As city living becomes increasingly less bearable, as we are no longer able to shower or water our tomato plant and as rural living becomes slightly less tedious, we make be shocked to see a landslide of people beginning to Re-ruralise. Of course, this trend will begin with the rich, but as we have seen with all technological change, these trends spread very, very fast to the poor. (Remember how cell phones were first just for millionaires and rock stars?)

No they wont. But I have a lot of fun making them : )

For a very long time the general consensus has been that progress equals Urbanisation. While I can see how the past that we come from relied on technologies and conveniences that were just not available to people in the rural areas, I can see now that a shift in technology (and its nudging along by Covid) has helped many of us to beginning to imagine a re-ruralized future.

I really quite enjoyed this piece below that speaks to some of the key drivers in re-ruralisation thinking.

Architects of the world, please remember the buildings and landscapes you design are habitats for wildlife too. Swallows must make their nests, bees and butterflies must do their thing! There is room for all of us on the planet. It just takes a little mindfulness in the part of decision makers.

Though it really seemed impossible to me at times, I have eventually settled in back at the cottage at Pebblespring Farm. I had set for myself the clear intention of having Christmas lunch with my family at the cottage. I am happy to say, we achieved this objective.

Its been a lot of work getting the cottage into a semi-livable state again . I am not at all happy at all with the way in which the tenant I had treated the place. But I get the sense now that we will chip away at this project in our own time for as long as it takes.

There is something deeply satisfying about being here. Committing my energy to projects that feel that I “own” in someway. I am not exactly sure about why it feels so good, but the “why” of theses things is never really as important as just observing and taking note of the energy as it presents itself in my body and in my sense of well being.

I have been resting as much as I can in between the various cottage and farm projects. In my resting time at the dam in the morning, with my coffee, I have time to think a little. This morning I spent some time thinking about the work I love doing on the farm and in the forest. I notice that this work, over the last few years, has largely to do with taking away what I don’t want. It has largely to do with “subtracting” and not to do with adding. When I am working with the chainsaw removing the alien invasive Inkberry (Cestrum laevigatum) or the Long Leaved Wattle (Acacia longifolia), my strategy has been to remove what I don’t want, quite surgically, then sitting back and watching as the new forest, new life and new beauty emerges. In the forest, I do not plant the new trees. I do not introduce the new life or the new beauty. It simply rises up, as if by magic, after my work of removing and subtracting what it is that I did not want.

When I take the time to sit and think, I notice how so much of what is going on in my life, with Pebblespring Farm for example , is some kind of metaphor, as if though,(in ways I can not possibly understand) my life is “fractal”, where the part reflects the whole and the whole reflects the part. Let me explain what it is that I think I mean. I can see that in my life my task becomes to remove those elements that do not suite me, that are not beautiful to me. Because my life, this existence, what I experience as reality is a living dynamic organism. The forest has a life of its own. It creates new and beautiful things all the time, especially if I can just help it along be subtracting that which is not good and which is not pleasing. (if the forest were pristine, and not infested and invaded by unnaturally introduced alien species, I would of course not need to intervene at all!) The forest is not inanimate. I must do my part, but the forest responds by making making beautiful spaces and views and habitats. I did not make these beautiful things, but here they are, clear as the light of day. And so perhaps in my life, I must be less anxious about what new stuff I feel I should build for myself, but rather spend time focusing on what it is that I must subtract.

I have seen that there are people that have followed a path of “spiritual” discovery that took the dramatic step to remove all the things from their lives. In the ancient way of the Sharman or the Monk, they give up all of their possessions, their loved ones, everything that they may have valued. But is this not perhaps the equivalent of bringing bulldozers to Pebblespring farm and flattening everything down to barren sand and rock. (Incidentally this is exactly what my late neighbor, Richard Hall, did next-door about five years ago at his place and I can tell you the land is lifeless and dead to this day.)

That is not the path I have chosen for Pebblespring Farm and that is not the path I have chosen for my life. Rather than flattening everything I have chosen rather to specifically and surgically remove those parts that do not work for me. In my life and at Pebblespring Farm I have also not opted for an “anything goes” approach. I do not just let the unsightly alien invasive bush take over, I do not allow my life to be taken over by social media or booze or carbohydrates or people that abuse me me. Perhaps the way I have chosen is a “middle way”?

In spite of all of what I have already subtracted, I am acutely conscious that there is still a lot in my life that does not work for me. Commuting does not work for me. Mindless admin does not work for me. Inhuman bureaucracy does not work for me. And people who do not love me. People who do not respect me. People who I do not “vibe” with. (“Vibe” is actually quite a nice word to use in this instance. It hints a the mysterious and unfathomable vibration that is beauty and attraction.)

I have already done a lot in the last few years to make my life simpler. (COVID has been helpful in this regard actually!). There is still a lot of work for me going forward to remove these unwanted aspects from my life. I am conscious that it will take a lot of time. But I must work methodically and consistently, but not so hard that I loose myself, and that I forget what I am trying to do in the first place. I must not allow myself to become so numb and so beaten that I cannot see the beauty. Because if I cant see the beauty, I will loose the energy I need to continue in the exercise of subtraction.

Perhaps I will report back on my progress here on this blog from time to time. Who knows??

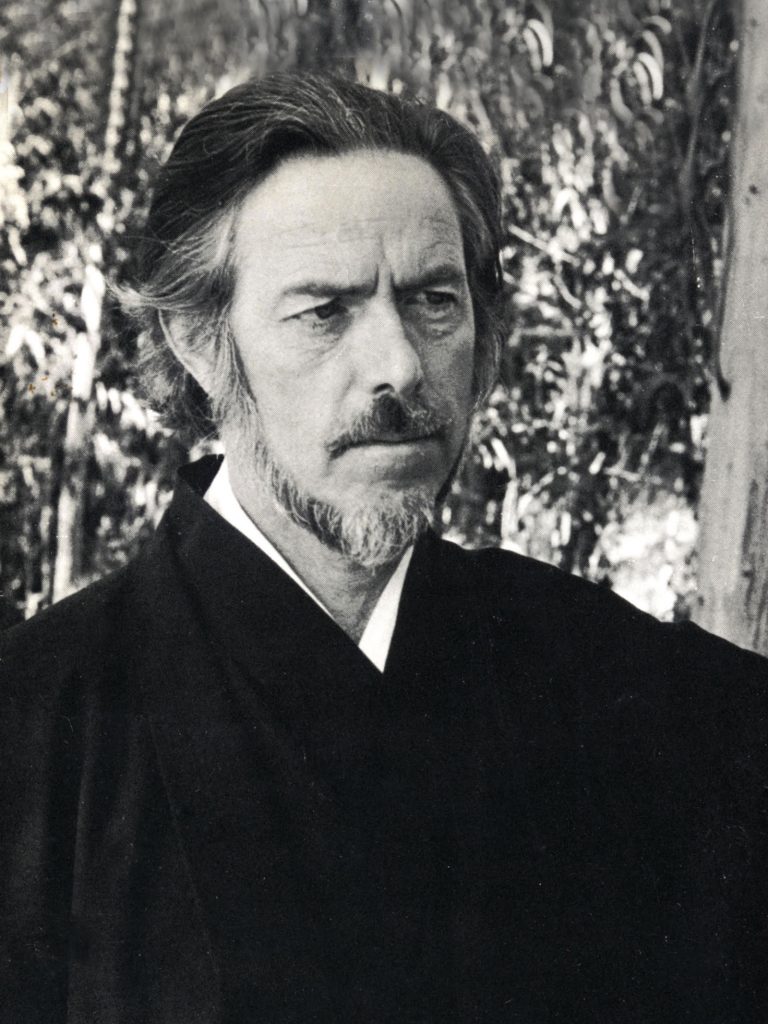

I have been spending evenings lately listening to Alan Watts. He has a whole bunch of stuff on YouTube, all recorded before he died in 1973, but lovingly uploaded more recently to the internet by followers from all over the world. He speaks so incredibly eloquently about matters of Zen and Tao an so much of what we says resonates very deeply with me.

What I am thinking of tonight is the phenomenon that Alan Watts speaks of in our tendency to for us to obsess about separating our “self” from the “other” and how actually if one looks closely enough, we begin to see how it is we are in fact a lot more integral with the reality around us than what we say we are. It seems to me that we make attempts all the time to play this game of separation: We see ourselves as separate from nature, even to the point where forget we are animals. We see ourselves and different and distinct from the thousands of gods we have embraced across many civilizations and cultures. We see our gods as the “other”.

We take this idea of “self” and “other” even further into the game we play within our own species where at a group level, we separate, our class, our religion, our nation as distinct from the other. We have often even made war along these lines. Killing and maiming ourselves in the process.

But is it not interesting to see that we are not happy to stop even there. Rather we insist even in our individual selves to create separation. We great a separation between our role as son and as father, as lover and as worker. We even wear separate “uniforms” at work and at home. We have a separate uniform for going to church and for playing golf, we even have pajamas as our “uniform” for sleeping. All of this in a desperate attempt to convince ourselves of the illusion that everything is separate. Well it is not! Everything is part of everything else. This is just the simple truth.

So in a small way perhaps, I see the move back to Pebblespring Farm and other lifestyle design steps I have taken, as an attempt to work against the drive toward separation. Because if there is no separation between work and home, perhaps it is a simpler task to get to a point where these is no separation between attraction and action or work and leisure. Where there is no separation between my health and the health of my business and there is no separation between the health of my business and the health of the people I employ and there is no separation between my prosperity and the prosperity of my clients.

There was a time when I was self conscious of over thinking things or sounding “too philosophical” But now as I am older. I am wiser. I realize that actually that is exactly the game I like to play. The game of “seeing the world in just one grain of sand” The game of treating what comes to me in my life every day as having some special, mystical meaning and significance just for me. Life’s just more fun this way! It makes me take everything that much more seriously!!!

1 October 2021

So, I have told you before about how what I thought was going to be a 3 week “camp” at the flatlet at my office for the Covid lockdown became a slightly extended affair. I very soon realized that I would not be able to get back to Pebblespring Farm any time soon. So, I made the very painful decision half way through last year to let out the cottage on the farm. I was relieved to find a tenant and was very happy to see that they were even able to do some small farming in the time they were there. If I had left the place unattended I have no doubt that it would have been vandalized and overrun by vagrants and poachers (in the same same way it was when I found it before buying the place). As we speak though, the tenant’s 12 month lease now comes to an end on the first of October and I am eagerly counting down the days until I can restart my adventure at Pebblespring Farm.

But some things have changed in my thinking over the period of Covid and the various categories of lockdown we have lived though. Firstly, I have really gotten quite used to the idea of living where I work. While I know that for many people across the world this has meant that they have been able to work from home, for me it came to mean that I was required to live at the office. But the point is that I quite like it that way. I quite like the idea of not having to commute. I quite like the idea of having only one internet connection, one armed response, one garden to rake the leaves up out of, one bathroom to keep clean, on fridge in which to keep the milk for my tea…… I think you follow my thinking here.

So as I write these words (and perhaps the reason I am writing these words) is that I am thinking through the detail of my next step. What I am sure of is that I will begin to get the cottage ready for me to move into it as soon as the tenants move out. What I am equally sure of is that I will then move back to the farm. What I am not sure of is, if, how and when I will get the office to follow me there. There are a number of things to think about:

1 – I will have to beef up security here at my office, if the dogs and I are no longer sleeping here. But this is of course a short term problem. While I can see that there may be a transition period where I am again sleeping at the farm and commuting to the office, the idea is to remove myself from the the Walmer property completely. (if I do remain involved with it, it will be as a developer and and investor, not as a tennant)

2 – My colleagues working for me, may not be too happy about commuting out to the farm every day, but then again its only 20 kms or so and it is against the flow of traffic. I do quite like the idea of physically working together in one space for a good portion of the day. While I have found that during hard lock down, we could work apart, I see that there are definitely some efficiencies that come from us being just a “shout over the shoulder” away from each other.(in fact I am even a little worried about making this post because – I have not yet sat down with and spoken through the detail of the move, mainly because I am not clear on the details)

3- What I have noticed is that the need for a boardroom for client meetings has drastically reduced. And also, if there were a need for a client meeting, it can easily be redirected to another venue (what I am saying is there would be no need to inconvenience clients by having them drive out all the way to Pebblespring farm for a meeting.)

4- It is also really quite handy to have an easy to reach address (like sixth avenue Walmer, where things can get dropped, either by Takealot or Checkers sixty60 or by clients, contractors of suppliers)

5- Then the other concern I have is the “what will they say?” concern. And I suppose that is one of those questions that lurks in the back of my mind and then once I expose it to scrutiny kind of evaporates. Who is the “they”? Why do I think that “they” will have anything to say at all? I do suppose there is something to say for PR – It would not be useful to me in business if the “talk” was that my moving out of Walmer was to be understood in some way as me closing down or scaling down my business.

6 – There are a whole lot of things that I like about living in Walmer – I like to be close to the gym. I like the place where I drink coffee in the mornings. I like the fact that I can get things delivered quite easily here.

So if those are the top 6 things that are bugging me. Let me think through here what options I have.

Firstly I think it is important to have some presence in town. I suppose I can achieve that by partnering with a friend in business – Perhaps put up some signage at their office gate – so if someone were to drop something for us they would see us. Maybe even a place where one of us could work for a short while, though, I think a coffee shop is perfect for that. Or perhaps we have no presence at all (in terms of signage) – We simply have a “drop box” an address in Walmer from which things can be collected or at which things can be dropped. The more I think of it, the more that I see that it is really not a very big issue.

There may be a need for a boardroom table from time to time, but these events will happen with such advance notice that theses meetings could very easily be held at the offices of a friend in business or at at coffee shop, or in extreme case at hired meeting spaces.

The problem of my colleagues commuting: The obvious answer there is to clear my vision in my head as best as possible and then to sit down with each of them individually and work out a solution. It may be that I need to increase a salary slightly to accommodate the increased monthly fuel bill. It may be that I would need to agree to greater “work from home time” I don’t know, but the meetings will guide me.

Then there is the matter of what is the PR message here? And I thing that can play out very well. I think the idea can be celebrated as a time appropriate response to the times. I can be celebrated as a leveraging of the technology that we not have to begin to live and work more where we choose and not where we are compelled to because of convention. Yes – I think I can get this message out there in a way that it is seen as positive and progressive.

But on a personal level. What do I do about my gym routine? What do I do about my coffee routine. I quite like the light an loose social interactions here. I don’t see myself driving all the way in the morning to the gym here. That would be counter-productive. I suppose the answer is, we will just have to see what new routine and rhythm grows up out of this change – and you know what – worst case scenario – move back to Walmer – for heavens sake – all of this is undoable!!

The true story of one common soul’s search for his own nobility.

Tim Hewitt-Coleman

April 2020

These few essays are not about the Tao, nor are they necessarily about farming, but rather I would say it is about freedom. I would say it is about coming to see how your and my freedom has been slowly and systematically taken away and more importantly it is about what actions you and I can take today to reclaim this lost freedom. Because you, like me, are probably living a modern urban life. You probably have a job. Your kids probably go to school and you are probably paying a mortgage bond. In all likelihood, you have a routine of working at a job during the week and taking weekends off to do the things you like to do or perhaps even just rest enough to be able to face another workday at your job that you dread going back to on Monday mornings.

The reason you, and me and other people we know put up with this routine; this pattern, is because “everybody knows” that there is no other way. “Everybody knows” that this is the best we can do, and that we are far better off than those people starving in Somalia, who do not have a modern economy that affords them the luxury of having a job and being able to send their kids to school. Even in your own city or town you see that you are better off than the guy on the street corner begging for coins or the people we see on the news that are dying from Cancer, Aids or Diabetes. In this way we begin to censor ourselves. Censor our own thoughts. When, in the rare moment, we are not numbed by TV or beer, we hear the faint thought that asks: “Is this all there is?” or “Does it have to be so hard? We immediately censor the thought as self-pity or as outrageous, stupid fantasy. We crack open another beer and flip through the channels. Confirmation and comfort comes in the form of explicit graphic images of some war ravaged, disease infested shit hole somewhere in the world that is much less comfortable than your fake leather couch. “And anyway there’s a match on this afternoon, let’s see when that starts”.

My programing, my default view, has therefore become, “this is just the way things are”. Go to school, get a job, have wife and kids, stick with it, it will all be over soon and then I’ll die. Your programming may be like mine. I suppose the belief I have somewhere in my sub-conscious mind is that this is a “Law” of sorts. Perhaps like the law of gravity or the law that governs the speed of light. It’s just there and to push against it is just a futile waste of time that makes everyone unhappy. This law of “the way things are” does make provision for one or two of us to be rich and have more stuff. This requires hard work, luck or the risk of prison. So you, like me, have probably opted for hard work, because we know that we have no control over the forces of luck and we fear that our families would be uncared for and unhappy if we end up in prison!

As it turns out, we are now made to understand that the very way we are living (this way of living that makes us so miserable) is also the cause of massive, probably irreversible damage to the planet. The way we live uses up huge amounts of fossil fuels sending millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere, where it will probably, for come complicated and technical reasons, cause global warming and destruction of all the ecosystems our history has ever known. The way we live, we are told, is also causing billions of people to live in real poverty, with real starvation (the kind where there is no food to eat). We are told that because of unfair international trade, or urbanisation or global financial turmoil, or over population, that these people are required to face a miserable future. So, in summary, because of the “middle class” urban lives (that make you and I miserable), we have a sick planet with a lot of starving people. This “inconvenient truth”, makes us even more miserable, as we find that the very lifestyle that is making you and I feel trapped into, is also devastatingly destructive and completely unsustainable. So, on top of our boredom with the nine to five, on top of our frustrations with uncaring, machinelike corporations and institutions, we now have to deal with the guilt of destroying the planet. But we do deal with it, we do move on, because we know that this is “the law”, this is “how things are”. It’s like the “law of the jungle”, “survival of the fittest” and “dog eats dog”. I reassure myself that there can be no other way.

But what if my middle-class urban existence is not the inevitable reflection of a series of predetermined laws? What if there is another way? That’s the question I ask in this book. I ask this question now, at this time, because it’s been something I have been thinking about a lot the last while, especially since 2014, when I bought Pebblespring Farm, a discarded and marginal 10 hectare piece of land on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth. There is something that attracts me to live on a farm, and something that has attracted me to this particular site. I see in it so much beauty. When I am on the land I feel a deep love of the place. I don’t understand it completely, I am just sharing with you that there is some kind of strong and positive emotional connection to the land. And also perhaps that the beauty I see at Pebblespring maybe be something that not everybody sees. The reason I suspect that this is the case is because the farm has been abandoned for probably 20 years. No one has seen enough beauty to convince them to make the purchase. I did make the purchase. I was able to do so because, in line with the law of the middle class, we were favoured because of hard work and luck.

The point though, is that working with this land over the last year has led me to ask:

So I ask the question:

“Have we forgotten THE TAO OF THE FARM?”

But why am I talking here of the Tao of the Farm, but not of the law of the factory? Why not the law of the butchery or of the bakery or the law of candlestick making? What is it about the farm that makes it significant? Why not the law of the hunter or the law of the gatherer? I would say that I am pondering the Tao of the Farm because farming is not just another job or another way to make a living. I see the farm rather as a concept of how to care for the earth. When we, as humans, invented the idea of the farm, we began for the first time to explore the possibility that we can live on this planet by caring for it not just taking from it. We began to explore the idea of being custodians of a small patch of land and looking after it in such a way that is houses us, clothes us and feeds us. To this day all of us, anywhere in the world remain part of the farming idea and the farm economy every time we eat breakfast, lunch or supper. Every time we wear cotton or leather, every time we put sugar in our tea or cream in our cappuccino. But today of course, what we call farms and where we get out food is very far away from the early ideas that gave birth to the concept of farm. Contemporary farms resemble factories or mines. Factory chickens, factory pigs, poisoned orchards and mechanised milking parlours. No, this is not the picture I hold in my mind when I consider the Tao of the Farm. Rather the picture I have is the small, mixed use family farm that I know from nursery school stories of the English countryside with Peter Rabbit, old Macdonald and Postman Pat. The picture in my head is of the farms that I have read about in China, Korea and Japan, where small patches of land have been farmed productively and continuously for the last four thousand years and farmed in such a way as to add to their fertility and to their biodiversity. This is the picture I have my head when I speak of the Tao of the Farm.

The idea of the farm has of course been hijacked by feudal lords in Europe, Central government in China and more recently the massive corporations of the US and of international capital. In many ways the “agri-business “has come more and more to resemble the attitude of the hunter gatherer. “Let’s take all we can now and hope it grows back”. This strategy was of course completely appropriate to the hunter gatherers that predated the invention of agriculture because the populations were so sparse that there was never really a problem when we needed to move on to the next virgin forest or wide open savannah when we had killed of all the mammoths or fallow deer or whatever it was we were harvesting form the environment. The difference, that of course any grade three can point to, is that once agri-business has poisoned the soil and stripped it of all its nutrients in exchange for a few good years of soya bean, maize, sugar cane or wheat, it cannot move on to the next wide open savannah or virgin forest. We are all farmed out! New land is just not available at the rate that agri-business is destroying it.

So, to be clear, agribusiness does not understand the Tao of the Farm and agribusiness is not what I am talking about when I use the term “farm” in this book.

But what about the term “law”? Well, in my work and career as an architect I have come to see that understanding the “law” does not limit or inhibit creativity. I suppose law would be the opposite of creativity, if all I did was to learn the laws and then live in fear of breaking them. But I have come to see that by learning the law of the brick, its properties, what loads it can bear, when it will crack, what weather it can resist, I come to be able to shape it, to create walls of many shapes, housing many functions. And so with the law of glass, the law of timber, the law of oil on canvas, the law of steel and aluminium. By knowing the laws of materials and components and by knowing how they respond to each other, the skilled architect is able to make beautiful spaces out of plain objects. In this way too, for me to build a life that is rich and beautiful, I have to make every effort to discover what are the “laws” that govern how things are. What are the fundamental properties of modern existence? Because if I know these laws I can design a life for myself, my family and my community that is beautiful and that is so much more than the stuff, the resources, the materials we have employed to build it.

What follows in these pages is not an attempt to hand down a new list of laws. Like Moses tried to do when he came down from Mount Sinai. No! Not at all. Rather, by just reflecting one small part of my own life experience, and pointing to the obvious ”laws” that reveal themselves there, I know that I will open your heart and your mind to the possibility that your sub-conscious has been sold the idea that our lives are governed by a whole lot of laws, that we can actually consciously replace with a whole lot of more useful ones.

This is my wish for you.

Tao of the Farm – Principle Number 1:

“One plus one equals three.

In the last few months, I have been planting fruit trees and nut trees on the farm. In between them I have been planting berries. I have taken quite a bit of effort to prepare the land using a system of swales constructed on contour that will help to retain moisture and soil nutrient. As these swales weave their way through pasture and bush, I have cleared to unwanted invasive species and have used their timber in the base of the swale mound to form the basis for composting that will take place over time. It’s a very old system of planting and I have done what I can to read as much as I can about it. But regardless of the preparation I have done for my apples, mulberries, figs and lemons, it comes down to digging and hole and planting a tree. (One hole plus one tree). Every one of us knows since we were two years old that one hole plus one apple tree does not give a hole and a tree, rather it gives and abundance of apples, shade, blossoms, wood and pleasure for a hundred years. In the case of the apple tree one plus one does not equal two. It equals two million perhaps.

I suppose one hole and one apple tree does only equal a hole and a tree in some laboratory somewhere, which will control the environment in such a way as to ensure that there is no sunlight causing photosynthesis, that there is no water in the soil to feed the roots, that there are no organisms to transform the organic material into beneficial nutrients. Then I am sure the tree will not grow, proving that one plus one does equal two. But thankfully we do not live in that laboratory. Where we live and where I plant my trees on the farm one plus one does definitely not add up to two. But where we work and where we play out our middle-class lives, those that try to sell us stuff or buy our time present “one plus one is two” as a fundamental law of the universe. One month’s work equals one month’s wage, because “money does not grow on trees” One hamburger can be bought for the cash price required of one Hamburger, because “you get nothing for nothing”.

There is of course nothing wrong with arithmetic. On a chalkboard, in a grade one class, one plus one must remain two, but in so many other situations the law is not useful to us at all. It is especially not useful to us in the way in which corporations and institutions make every attempt to make us believe this law in order to remained trapped in the systems that they need to keep us trapped in, using schemes like:

Now, let me look at my own life. What can I do with my new understanding of the law “One plus one equals three?” Not everyone has a farm on which plant apple trees of course, but what can we do that will show massive dividends later? What can I do today that has a lasting impact that does not require me to labour over it day and night? What lasting things can I do today, that keep on paying dividends? What if I did one thing a week that would have lasting impact? So much of what we do is wasted. If I wash my car today, I have to wash it again tomorrow. If I watch TV tonight, I have nothing to show for it in the morning. But if I tile my bathroom, or arrange photos in my photo album, or paint a picture, or write a poem, these things are lasting and keep on giving much more than once. This is where our focus must be. Where we must do things or buy things that are temporary, let’s set a rule. Let’s not buy anything that will not last five years. Be it shoes, or a jacket or a cap or a skateboard. Let these items keep paying dividends for years. Let’s make a rule to cut down on those things we spend time and money on that don’t deliver dividends. I am not saying you should not from time to time splash out and have a great steak at a restaurant, but to invest time and money in drinking a R200.00 bottle of wine every night is to become addicted to a passing pleasure that could rather have been a lasting gift.

The Fashion industry is capitalisms mechanism for making us all believe that we must keep on paying. Fashion tries to get us as close to the ideal of “use it once” as they can. I know women that will not be seen in public wearing and outfit that they have already been seen in. (I am sure that there are men who behave in this way, it’s just that I have not yet met them) The fashion mind-set began with clothing, but there are clever “marketing gurus” that have managed to shift the focus into music, automobiles and electronic devices. I am not suggesting that the new car is not better than the old one. I am saying that we are motivated to buy the new gadget only partly because it is better and largely because it is more fashionable to do so. What I am saying is that the iphone 3 is a fantastic piece of technology. There are very few practical reasons why we could not allow the gift to keep on giving, but we don’t allow it to do so, we buy the iphone 4, then the I phone 5, then the iphone 6. We do this because we are not open to the idea of investing once and then allowing ourselves to receive multiples of one. We are not open to the idea that one plus one can be equal to more than two.

In relationships we are the same. We limit ourselves. We do not invest in a handshake, or a smile or a bit of meaningless banter with a stranger, because “it’s not worth the effort” We expect in return at best only a smile, or a handshake or a bit of meaningless banter. (at worst we fear that we won’t even have the smile returned, and we will be left in deficit) If though, in our minds we can begin to expect, even demand, that a smile will be returned as a smile and perhaps a warming chat, or an exchange of useful information, or a hug, or a kiss, or a lifelong relationship including seven children and big house in Plettenberg bay, then we will begin to receive those in return. We must though, begin with the expectation that it is absolutely normal and natural to receive a lot more than we give. That is the way of the living universe. That is the Tao of the Farm.

Tao of the Farm – Principle number 2:

“If your hens don’t lay, you can’t eat omelettes.”

I have been struggling to get our chickens into proper accommodation. I moved them to the farm a couple of months ago already now as part of a massive back yard clean-up campaign in the build-up to the big party we had at home toward the end of last year. The chickens were hurriedly put into a two metre by two metre box. Well it’s not really a box, more like a frame, a box without a top or a bottom. It was built hurriedly in July last year as a temporary structure to hold the newly born puppies that were running amok and getting themselves drowned in the pool. I am generally reluctant to throw good stuff away and thought it was very creative of me to re purpose the puppy box into a chicken box. I moved it to the farm, put a bit of chicken wire over the top nailed a little egg box in one corner and we were in business, we had a portable structure that we could use to pasture our hens. Moving them to fresh grass everyday where they can scratch and dig and set there manure down in such a way that it is a huge benefit and not a toxic problem requiring hours of our precious time to clean, cart and sanitise. And after all, we had tried pasturing poultry this before with broilers in the suburbs so I was pretty pleased with myself for the quick thinking re[purposing project. Taking a pile of old wood that was surely headed for the tip and turning it into an egg producing, pasture fertilising machine. Absolutely brilliant!

Except…

The mongoose, or whatever it was that found the pastured poultry pen on night number three, had other ideas. On the morning of day four we found a hen dead and with a hole ripped in its stomach and its intestines ripped out. On the morning of day five we found another hen, this time with its head gone and a similar problem of missing intestines. The best that I could figure is the chicken thief was squeezing under the frame in the small gaps between the timber and the grass. It was killing and eating inside there and then getting out the way it came in after it had had its fill. I was deflated. You and the family were kind. You only went on with “why didn’t you just…” and “wouldn’t it be better if?…” for about a week. I was let off lightly. But we did find a solution, after reading the farming a permaculture websites and forums, I came across and American farmer, Joel Salatin’s suggestion that foxes on his farm are discouraged by a metre wide “apron” of chicken wire around the pen. Apparently the fox is not bright enough to know not to start digging a metre before the pen to dig under the apron. I tried it out and yes it works (on what I still only suspect is a mongoose problem.) The chickens have survived every night since then, but still no eggs. I am not sure what the problem is, perhaps they are being harassed so much every night that they are too stressed to lay? Perhaps the ratio of roosters to hens is now wrong (since the mongoose took hens and not roosters? I don’t really know. But there are no eggs.

Now to make matters worse we have puppies in the house again. Our beautiful mommy dog, a gracious, gave birth to 11 lovely puppies, five weeks ago. This week one little puppy accidently got out of the secure area and stumbled into the swimming pool and drowned. Everyone was in tears. We had a crisis. I have been having a busy time in the office so the best solution we could come up with is to hire a trailer, go fetch the puppy box, which has now become hen box and turn it back into a puppy home. This is what we did. The problem of course is that the chickens are now in very temporary accommodation and I am hoping will all survive the sly mongoose until tomorrow, Saturday, when I can spend the morning making more permanent accommodation for these incredible animals.

In a roundabout way, what I am saying is the seemingly simple task of getting eggs from the chickens actually takes a lot of care, effort and management. Those that do it well make it look very easy. I soon will become one of those that make it look easy. But right now, even though my hens are not laying, I am still eating omelettes. Through some fortune, I am able to sell some other goods and services in order to get money to buy eggs. There is nothing wrong with this system of trade. In fact it is a very clever mechanism; it can though cause us to begin to create in our minds a distorted view of reality; a view that dislocates the desire to eat omelettes from the desire to learn how to care for hens. Our system can create an illusion in our minds that in some way those that live around us, in the same city or the same country owe us omelettes or owe us a living. That we are somehow entitled to be given stuff.

Giving is a very good thing to do. In fact, I make the effort to give as often as I can, especially to people I can see really need help. But when I give, part of my duty to the person receiving is not to allow his mind to be poisoned with some irrational belief that he should expect me to keep giving to him. If I fail in my duty, he may come to forget that it is a fundamental law of how things work that you have to put in the effort, physically, mentally and spiritually. He may come to forget Tao of the Farm – Principle number 2: “If your hens don’t lay, you can’t eat omelettes”. I may even have left him worse off that when I found him if I don’t take the effort to help him see this. So, in my life I try to remind myself, as often as I can to stay real in that way. I try to stay observant. If things are coming too easy, yes, I celebrate, but no I don’t take it for granted. I don’t expect it will stay good forever, because I know time will correct the situation because of the fundamental laws that are in place. If I have not made the effort, then I should not expect any reward. If something has come my way out of luck, I count it as a windfall, a lucky break and I make every effort not to allow my mind to expect it to happen again. This is the Tao of the Farm!

Tao of the Farm – Principle number 3:

“You can’t become a shepherd by reading about sheep”

Perhaps a real adventure is one where you really don’t know where you are going to end up. I can see now that our adventure of perusing the farm Goedmoedsfontein has been just such an adventure. I am still not completely sure where the adventure is going to lead, but for better or worse we have caught the train and we are headed out of the station.

In March 2013 I secured and option to purchase this beautiful 10 hectares. It has spring, a stream and a dam. It has some forest, some grassland and some marsh. It is just the right distance from town, in the country, but still allowing our kids to go to school in the city. Just close enough for people to be able to drive out to the farm and buy their weekly supplies of eggs, chicken, boerewors and other fresh produce we dream of marketing from the little shop (or a ruin of a shop that we intend to renovate back to a shop) that is on the farm.

We managed to sell some property to raise the cash that helped us secure the difference between what the bank would loan us and what the sellers wanted. The funny thing is that I didn’t feel so much that the “train had left the station” when the sellers accepted our offer, or when the bank approved the finance or even when I paid the deposit to the conveyancers. In fact, I only felt it on the weekend we brought nine of or our cattle to the newly purchased farm from where we were keeping them in Tsitsikama (a hundred and fifty kilometres away to the west)

I had worked hard the week before to create fenced pasture for them. It measures about 40 by 60 metres. The pasture is good. I rigged up a water supply from a rainwater tank which I haphazardly installed to catch some runoff from the roof of the cottage. We loaded these cattle up on a hired trailer on the Saturday afternoon and drove them to the farm. It was the first time had loaded cattle or pulled them on a trailer. It was quite scary. Number one it’s a heavy load and you can’t go very fast and number two these guys kept jumping around causing the trailer to sway uncontrollably. It was not fun.

After this exhausting journey we got the trailer as close as we could to the new paddock (but this was still the other side of the stream). We let them off the trailer and they scattered in all directions. If my son, Litha was not there I don’t know what I would have done. But we eventually got them herded together and moving slowly in the direction of the paddock into which we managed to secure them. I was exhausted by the time I got home, and a bit shaken by the experience. The next morning, Sunday, Litha and I drove to the farm. All nine seemed quite restful. Some were mooing for their mothers (even though they were quite a bit over 12 months old they had not been weaned at Tsitsikama) All seemed fine, but when I came back on Sunday afternoon, I found the whole herd out. I was alone. I ran around like crazy at first trying to direct them back, but they were determined to get away from the paddock. I called my neighbour, Richard. Luckily, he was in he and a friend came to help. We got them in, and I spent the rest of the evening trying to make the fences more secure. But the more I tried the more I could see that two black cattle were absolutely determined to escape they pushed at the fences and then over they went. By this time, it was about 8 pm. I called Litha. I stayed by the fence that had just been jumped to be sure the others would not also come out. They did not and eventually the you and the family arrived and herd to two black cattle back from the tar road where they had got to so that I could get them back in the paddock.

With family back home preparing for the first day of school the next day, I sat in the dark at the farm watching the fence, stepping up every few minutes to beat a cow back from the fence it was trying to trample. It was a losing battle. By about 10 pm as the rain was starting to come down, the two belligerent black cattle again jumped the fence. I had no choice but to let them go. I was hopeless to try no again to find them in the dark and what’s more the remaining seven cattle seemed reasonably complacent and not intent on leaving the paddock any time soon. I went home, defeated and depleted, to sleep. In the 20 minute ride back home I could not shake the stress. I was upset. I was rattled and I was exhausted. I did not sleep well. My mind was racing, fearing the sort, fearing the whole herd was now dispersed all over the neighbouring farmlands. But I knew there was nothing that I could do till the morning.

I left home at 5:30 am. I found a job seeker next to the road near the farm before 6 am (I could not believe my luck that there would be someone there that early – his name was Marius) Marius and I found the two black cattle heading toward us on the side of the road. They were reasonably easy to herd back and seemed quite relaxed and content to be re-united with the group they had abandoned the night before. I was relieved that the others had not also jumped the fence. Marius worked the whole day with Boyce to get the fences as strong as we could get them. I had to go in to the office for some crucial meetings. By the time I got back to the farm in the afternoon the cattle were all still in, but the two black cattle were mooing loudly again and looking agitated. As sure as anything right in front of my eyes the two black cattle jumped the fence again.

Richard from next door gain came to my rescue, suggesting that we separate the two black cattle out. He arranged for them to be located on his neighbours land were 2.4m high electric fence contained them that night. I kept the remaining seven on my side that night and set up the portable electric fence for the first time. When I went the next morning to drop Marius, they were happily inside the paddock. As I write this now at home 20 km away from the farm, I am feeling less anxious about the cattle on the farm. I don’t feel anxious about them at all. A year has passed since I brought the cattle to Pebblespring, but I look back and see how bringing them there definitely jolted me into a place in which I was uncomfortable. This was not theoretical anymore. I was not a spectator to the spectacle.

I had read a lot about cattle. I had quite liked Joel Salatin’s book “Salad Bar Beef”, I had tried to wade through Alan Savoury’s “Holistic Management”. I had even ventured beyond the printed page and run some cattle down in Tsitsikama by proxy, with other people doing the dirty work. But reality of this experience was large and in my face. It threatened my resolve, it got me thinking an doubting in a way that no book could do, because at the end of the day there is no way we can ignore Tao of the Farm – Principle number 3 “You can’t become a shepherd by reading about sheep”

But you know that I do not want to talk to you about sheep. You know that I am trying to point out how you and I can benefit significantly from getting out hands dirty with real experience, real risk and real discomfort. Of course, we must read, of course we must research, this is what distinguishes us for the other species, the ability to learn from each other and from generations that have passed. But there has been no generation like this one, so completely obsessed with media, so completely obsessed with reading writing, watching and listening. So much time spent spectating and only perhaps commenting, when we feel energised and confident, on the spectacle. We have become consumers of other people experiences and other people’s lives.

What do I say to all of this? Just don’t fall into the trap. Rather do something, take action, physical action. Run a race. Play and match. Climb a mountain, chop down a tree, plant a tree. Sure, talk about it if you have done it. Write about it if you have done it. Post videos on Youtube if you have done it.

But first do something!

Tao of the Farm number Principle Number 4:

“You are not the first person to plant a lemon tree”

As I write this, I have just returned from a weekend visit to “Babylonstoren”, a beautiful wine farm somewhere between Paarl and Stellenbosch. It has beautiful vineyards and fine examples of historic Cape Dutch architecture, but more than anything else, it is the gardens that leave a lasting impression. The three-hectare garden is expansive and is set out as a long rectilinear grid and irrigated with a water channel that runs along is length down the gently slope.

The gravel pathways form blocks which frame different zones of fruits, vegetables, poultry, herbs and flowers. It is a beautiful place, but at the same time is a fully functional, productive garden producing the highest quality produce for the three restaurants and shop on the site. The gardener is highly knowledgeable, as have been the gardeners that took care of gardens just like Babylonstonern in the cape since the time on the Company Gardens in Cape Town in the 1600s. The point of course is that gardening is not something new. People have been perfecting this art for thousands of years. Each generation of gardeners has worked to make slight improvements and modifications to the work of the previous generation. No successful gardener has ever plunged themselves into an open field armed with only muscles and a spade. Of course effort is the key ingredient. But in as much as the Tao of the farm – Principle Number 3 is true when it says that reading about sheep does not make you a shepherd, it is also true that there is a huge volume of information available to be passed on about any conceivable subject, including becoming a shepherd and including planting a garden.

At Pebblespring Farm, I have planted one or two lemon trees, but I simply don’t have 10 years to wait to see if this particular variety grows well in the particular spot I have chosen for it, with its particular soil and moisture characteristics. To short cut this process, I talk to other gardeners, I read books, I Google, I travel to Cape Town and visit places like Babylonstoren. Why? Because it’s all been done before and if I am thorough in my research, I will be sure to able to take advantage of the learning hundreds, perhaps thousands of years of lemon tree planters across the world. By playing my cards right I can obtain the power and clarity that would otherwise only be available to me if I had lived for many generations.

This is of course true whether I am interested in planting lemon trees, learning the art of Kung Fu or the craft of knitting a jersey. Invariably what we are trying to do has already been done, and if we look hard enough, we are able to find the stories of those that have done it. I have seen though in my own life, that finding the information is not difficult. What is often difficult for me is that, faced with the huge quantity of available information, the process of trying to consume it becomes all consuming. The balance between research and action becomes distorted and I end up binging on information: books, movies, travel, blogs tweets and Facebook pages. In the same way perhaps as the obese load up with so much energy giving food that they eventually become so heavy that they are not able to move to use up the energy, causing them to become immobile and to the point where the only action they are capable of is to take in more food.

My view then is that we must rather be led by action than be led by research. Let us push forward with our mission to the point where we can see that we can no longer advance because of our lack of knowledge. We will know when we have reached this point because a question will begin to formulate in our mind. We will start digging the hole for the lemon tree, and a question will begin to formulate. “How deep should this hole be?” Once we know the question, it’s quite easy for us to know where to look and to find the answer. The research then directs our next action. We dig the hole to the required depth only to be faced with the question of soil preparation. Should we fill the hole with compost, or should it be manure? Do we need to increase the acidity; do we need to make it more alkaline? As we proceed in our action, we are prompted in research. The research then prompts us into further action. It sounds obvious I know, but actually what I am suggesting is completely in contradiction to our contemporary education system which at very least creates the impression in people’s minds that education and training is what happens in that part of your life before you start working. So we” frontend” twelve or seventeen years of schooling into a young life at an age where working is frowned upon and even illegal. Once this stage is over, we enter our working lives where research is most often seen as a diversion or a destructive waste of time to the point where Google may be disabled on your company PC.

But don’t worry about all of that. Rather you just be sure that:

· Number one, you know your mission.

· Number two, you take the first step.

· Number three, you recognise when you are stuck,

· Number four, you find answers to the questions required to get you unstuck.

· Then proceed, re-check to be sure that you are still on mission and repeat steps one to four.

You can’t go wrong!

Tao of the Farm – Principle Number 5:

“A Cow eats grass and produces Manure; soil eats manure and produces grass.”

Cows are beautiful to watch in the pasture as they munch away at the grasses that they seem never to get bored of. We only have two cows are Pebbeslpring farm. The land is big enough to take between 10 and 20 cattle, but right now the pasture is small with so much of the ground having been overtaken by the terrible invasive Port Jackson Willow (Acacia Saligna) and the even more nasty Inkberry (Cestrum laevigatum). The Inkberry likes the lower lying wetter areas and is poisonous to livestock. The cattle find the Port Jackson quite palatable. I will see them fighting each other to get to the port Jackson if I have just let them into new pasture. The problems with the Port Jackson, is it grows so dense that the cattle find it difficult to penetrate and the leaves grow high and out of reach because the density caused it to be too dark for leaves near the forest floor. Also, because the Port Jackson are so densely packed, grasses can’t grow on the forest floor, again not good for the cattle because they like grass much more than leaves. But also, with no grass or any other growth on the forest floor under the port Jackson, the soil on the steeper slopes begins to wash away in times of heavy rain. So, my attitude toward the Inkberry has been to remove it wherever we find it. We cut it down as close to ground level as we can. When it sprouts again we cut it again. Eventually it stops growing. The Port Jackson however, I have been more selective with. I have begun rather to cut them in such a way as too leave behind a savannah of sorts. Trees spaced in a pasture in such a way as to allow enough light for light to get to the soil and allow the grasses to grow. I have noticed that, at least in the summer months the grasses seem to be taller and greener in that part of the pasture near the edges where the trees are. I guess it has to do with the fact that there is a little less evaporation there because of the shade. Perhaps there is extra nitrogen there because the cattle lounge there to keep out of the heat, perhaps because the Port Jackson willow is nitrogen fixing, the grasses are able to absorb this critical nutrient near the tree and grow greener. I don’t really know why the grass grows taller and greener where the trees touch the pasture, but I know that it does, and my attempt is to mimic it to see if I can replicate the results.

Of course, all of this stuff about pasture is quite possibly more interesting to me than it is to you. Books have been written about pasture. Entire library shelves filled. The important thing to take from the pasture is that we are dealing with a living system. In a very real way, the cattle and the grass and the soil are part of the same organism. The grass has evolved to look, taste and behave the way it has because of grazing animals like cattle. Cattle have evolved size, shape and biology because they have evolved in the pasture eating the grasses that they do. In the same way the predators shape the herbivores and the herbivores shape the predators. But these are not just curious facts of anatomy and biology. These are fundamental truths, absolute laws that whether we choose to or not are a governing force in all of our lives. It may appear that I as an individual am a separate organism to the people around me and to the things that I consume and to the things that try to consume me, but in truth, with the perspective of evolution and of time I am not.

So much of what I see around me attempts to convince me that I am a separate organism, that I am able to survive even without the planet, that I am separate from the earth. The spectacular project to send a man to the moon, walk around up there and take photographs of the blue planet from that far off position, is one in a sequence of events since the beginnings of consciousness that have made us feel more and more comfortable with the argument that we, human beings, are a separate organism. Perhaps consciousness itself, in its infancy asks the question, “who am I?” Am I simply the effect of other causes? The newly conscious mind begins to see that it has a will of its own. It sees that it is not like the birds of the sky or the fishes of the sea. The conscious mind chooses what it will do. The newly conscious mind may then begin to see itself as independent completely of the ecosystem, of the environment of the earth. “I can fly to the moon! You see! The earth is not an organism, and I am not merely a cell or a piece of tissue of that organism. I am separate.”

Of course, the illusion of separateness of those on board the Apollo missions is evident to any 10-year-old who may ask questions about food, water and oxygen, but somehow the illusion of separateness endures.

So, when I sit in the pasture. When I observe the earthworm, when I appreciate the cattle, I let the picture remind me of who I am. I let the picture remind me that I am a part of an organism, an organism that is beginning to show signs of disease caused largely by people, very much like me, that they have somehow come to forget the obvious truth that they are a small (yet very important) part of a big organism. Perhaps the disease afflicting the planet is like the disease of cancer that afflicts so many of our bodies. A disease that killed my father. The doctors say that a cancer cell is a cell that has forgotten that it is part of an organism. It consumes energy and replicates, but it has forgotten its function in the organism it grows and grows until it kills the body that it forgot that it was integrally part of. The cancer cells form tumours that are fuelled by excess sugar. People form cities fuelled by excess fossil fuels. Tumours and cities behave in this way because they have forgotten the Law of the Farm Number 5 “Cows eat grass and produce Manure; soil eats manure and produces grass”

Tao of the Farm – Principle number 6:

“You can do it alone, but it’s better with family”.

As I write this I am sitting at the table inside the “long room“in the farm cottage. It’s a warm summer Sunday afternoon and we have been here since lunch time yesterday. But what makes this weekend different is that my family is here with me. You see, the cottage has now been repaired to the point where it is now just about weatherproof. (Depending on exactly where in the cottage you stand during a rainstorm) The cottage also has running water, lights that switch on and off and it has a toilet that flushes. (All off grid I am proud to say) These simple conveniences make it possible for my wife, my daughter, my sister in law and her son to stay over with me at the farm last night. It was the first time for my wife to sleep over here, so I count it as a bit of a milestone. The thing is though, it just feels better to me for me to be going about my chores, moving the cattle, feeding the chickens or watering the fruit trees with my wife and family here on the farm. Yes, we had a fun braai outside last night and a pleasant breakfast this morning, but for the most part it’s just about knowing that we are here together, not necessarily that we are having deep, meaningful conversation or helping each other physically. When, as I have been doing for over a year now, I work on the farm over the weekends leaving my family at home in town, it feels different. It feels more rushed, strained perhaps. As if though a part of me feels that I am stealing time from them. I don’t know. I have not consciously recorded thinking that I am stealing time, it’s just that when we are here together allowing time to pass slowly together, it just feels so much better. It feels very right. It feels as if though it were meant to be. So perhaps this too is a lesson from the farm, one of the laws of the farm, that are true to the farm, but true also to our civilisation.

Let’s think about this a little. Because the idea of family and its “usefulness” seem in some parts of the world to have become caught up in politics of polarity , where the term “family values” have become used as a code to mean, conservative, male dominated and religious. I am not talking about that here. Rather what I am observing is and process of evolution, where our species has grown to become strong and prosperous by holding together in family groups or perhaps larger clan groups in the time of our foraging forefathers. Other species have evolved in such a way so as to make them highly successful to live alone for the most part. On the farm here we often see bushbuck. Sometimes a big impressive grey black male, will reveal himself for a few seconds before bounding off into the forest. At other times the female will peer through the shrubs, smaller and brown. We have not yet seen them together, as a couple. It seems Bushbuck are quite successful at living apart from each other for most of the time. But the ducks that visit the dam are always in a family group. Sometimes there are four of them together, other times just two. I have not yet seen a lone duck on the dam. Ducks seem to be family birds. I notice that the monkeys are always in a group when they raid the ripening cherry guavas.

Of course, humans have big brains and an impressive amount of will power, we can chose to do many things that may go against our evolutionary programming. We could live completely by ourselves and we have proven it. Every now and then there is some record broken when some brave person circumnavigates the globe single handed in a yacht, even smaller than the previous brave person who did so. Of course, it’s possible. What I am working on though in my own life, is to observe in me, what are the “laws” what is my evolutionary programming? In order that I can embrace it and work with it. In order that I can understand when I feel down or lonely that it is probably that I am feeling removed from my family. And by contrast, perhaps the reason (or maybe one of the reasons) that I am feeling energised and reconnected with farm and with my life and with my mission, is that I feel I am together in this with my family. We are on a joint mission. We are working together. We work at different speeds and we need different things to make us comfortable and relaxed, but we are all on the same mission.

Tao of the Farm – Principle number 7:

“The Sun will set at sunset – regardless of what is on TV”

When I got home from the office last night, Hlubi suggested that we take a drive to the farm. She had a stressful day. Being summer, the sun goes down nice and late and the evening was pleasant after the light rain of the day. We lingered at home though. We did not leave straight away. No big deal, but Hlubi fiddled in the kitchen, got dressed, took a few calls and spent some time waiting for an item to come up on the TV News. By the time we got to the farm it was almost dark. We missed that magic time just before sunset, when the birds go crazy, when the wind has died down and the sky is filled with a special light. That time where everything feels slightly electric, poised, pregnant. We ate our supper at the farm. We boiled the kettle on the gas burner, made a cup of tea and then we were off back home again. It was nice and it helped me remember that this too is a law of the farm. The sun goes down at sunset. There are no extensions of time. There is no appeal processes. It does not matter how big a crowd you are able to muster in political protest; it does not matter how much money you have. The sun will set at it designated time. This is a law of nature and it is the law of the farm. Why is it important to reflect on such an obvious fact? Why? Because we have moved into an era where many of us are led to believe that there is nothing constant, anything can be negotiated, changed or postponed. We can “re-wind” television for heaven’s sake. We can get a re-mark on our test. We can return the crème bule to Woolworths if it was a little too lumpy. We can vote out our governments. We can sell our shares. We can divorce our husbands. We can enlarge our breasts and whiten our teeth. Those of us that are distracted and have little time to ponder may develop the world view that nothing is constant, that we as individuals are the centre of our universe and all can be modified to meet our desires and our feebleness. But the farm tells us that life is not like that. The sun sets at sunset. The apple ripens not when you want it to, but when it has spent the adequate amount of days on the tree sucking in the nutrients built in the leaves from the rays of the sun. The rain will fall when the clouds become too heavy for them to hold onto their moisture anymore. The rain will not wait for you to have brought the goats in from the field; the rain will not wait for you to have completed the repairs on the dam. The rain will come, ready or not.

Because there is a softness that comes over those of us that think that everything is flexible, and anything can be negotiated. A certain lack of urgency descends over us. Without an order or a rhythm, we descend in to a timeless binge of Xbox, beer and pornography. Nothing matters, everything is the same and “what does it matter anyhow?” We see this when casinos and malls are trying to trap us to give them our time, our money and our energy. They do all they can, they don’t want us to know when the sun rises, when the sun sets, when the rain falls or when the wind blows. The clever minds that run these awful places know that even a little contact with the absolute rhythms of the earth, like day and night, winter and summer, may jolt us back to a reality and out of the clutches of the trap that they have invested so heavily in constructing for you and me.

The farm gives a rhythm and an everyday reminder that something’s are just not flexible. Not everyone can live on a farm, but all of us can begin to live a life that puts in place some non-negotiable. How about a half an hour of quiet reading in the morning before everybody else wakes up? How about a 30-minute run or a few push-ups in the bathroom before your shower? How about 15 minutes quiet time writing in your journal with your 10 o’clock coffee? Do this every day. Make it non-negotiable, because you say so, because you insist, because you know that you come out of a line of ancestors that moved to a rhythm you have now been robbed of. Because you know that if you don’t give yourself this time, it will somehow be stolen, be wasted away to the TV, Facebook, beer, soccer and shopping. They win. You lose. They gain your life and your energy; you lose your freedom!

Tao of the farm – Principle number 8:

Two Tilapia tanks are better than one, Four tanks are even better

I have been growing Tilapia for some time. They are a fantastic fish species. I have only recently moved them to the farm, from where I kept them in the backyard in Walmer. I built a hot house for them, because they seem to do even better in warmer water. They survive in the wild in our region in the rivers and streams though; to I am not sure how much worse they would have done without the hothouse. At Pebblespring farm, I have now released the Grey Tilapia I had into our far dam. Other I gave to my neighbour Richard who released them in his dam. Richard’s have been in the dam through the summer and winter and have done very well. I released them as fingerlings no larger than 5 centimetres and he has been fishing them out pan sized. My plan is to not fish any of ours out until next summer; giving them time to establish and grow our dam is a lot more alive with bulrushes, edge plants and duckweed, so I am expecting even better results that Richard has had.

There are a whole lot a great things about Tilapia, once I start talking about them I tend to go on a bit. What I like most about them is that they are omnivores. In fact, they can survive almost entirely of a vegetarian diet. They love to eat duckweed. Duckweed (Lemna) in itself is an amazing species. It is a flowering plant that floats in the surface of the water. Apparently, it is the smallest of all the flowering plants. On a dam or pond, it would look like a green carpet, but on closer inspection you will find that the carpet is not a mass at all, but rather a collection of little plants including leaves, roots and flowers. One little plant will comfortably fit on a fingertip. These fantastic plants can grow very quickly if the conditions in the water are right. It is not uncommon for them to double their population within a twenty-four-hour period. The best part of all is that they are a very good Tilapia feed, or chicken or pig or cattle feed. I have heard it said that duckweed has a higher protein content that Soya Beans and that it is eaten as salad of sorts in Vietnam or thereabouts. I have eaten a mouthful or two. It’s quite crunchy and fresh, but a little tasteless to my tongue.

The next best thing about Tilapia is they taste great. I am a very fussy fish eater. We have caught too many great tasting fish in the ocean to be able to tolerate poor tasting fish. Tilapia is excellent, not at all muddy or mushy, but very good tasting. Other than that, they are on my favourite list because the species I grow (Orochromis Mossambicus) are indigenous to my province and because they tolerate a wide range of water quality and temperatures. Which brings me to my story here. Tilapia do well in tanks, and they are easy for an amateur like myself to attempt to grow. But even Tilapia need the basics in place. They need Oxygen, then need filtration and they need food. In fact in that order of priority. I keep my Tilapia in 1kl tanks salvaged from Industry rubbish heaps in town. I have noticed that while they can go without food for some time, especially when the water temperature is low, they definitely cannot live very log without the water being oxygenated. They can survive a longer time with a filtration system broken down, but if the electricity goes down and the bubblers stop working you could have only a few hours before the fish start gulping on the surface then die. I have lost fish like this a number of times. It’s a risk that comes with keeping fish in high density tank environments. One of the ways to guard against disaster is not to have all the fish in the same tank, rather have two tanks, with two filtrations systems and two aeration systems. It then becomes less likely that disaster will befall both tanks. Even better have four tanks, or forty or four hundred. Even better have each tank with a different species or strains. Equip each tank with a separate power supply for the aeration and filtration system; because safety does not just come in numbers, it comes in variety. One hundred fish in a two-kilolitre tank is not as good a two on kilolitre tanks with 50 fish each. By the extension of this logic, it is in fact much better to have the fish in a series of dams and ponds where there is a variety of temperatures, plant species, crustaceans, water depth and oxygen levels. Variety is what brings stability.